– John Berger, 1978

– John McDonald, 2015

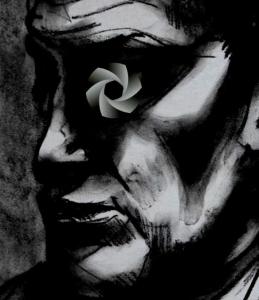

My photographer ex, not long before he ended our friendship due to confusion from cognitive impairment, would habitually criticise an acclaimed younger peer whose dramatic tonal contrasts he deemed ‘gimmicky’. Though chiaroscuro isn’t new (see Rembrandt), my ex equated printing sans special effects with artistic integrity. Yet his rival produced more dynamic images. My ex’s static (if formally satisfying) shots betrayed a lack of imagination.

Had I dared, I’d have said that if he aspired to represent the ‘truth’, using black-and-white film was hypocritical: we don’t see in black and white, except metaphorically; few of us even have black-and-white dreams. But he’d forged his career and identity back when black-and-white film ruled, and the photo monographs on his shelves were all monochromatic too.

The thing is, consciously or not, the self keeps changing. My ex’s rejection of new techniques kept him creatively blocked. Photos pretend to preserve the moment like a bug in amber, yet a sequence taken over time can foreground change: light brightens and ebbs, flowers bloom and die, trees fall as buildings redraw the skyline, our minutely monitored lives flash by…

Despite two years of photography as an elective at tech, I can’t recall, beyond how to use an SLR and a darkroom, what the teacher imparted. I think he just showed slides and left us to it. The scope was vast. You could record hardship, suffering, signs of violence, social change, faraway places, man-made disasters and freaks of fate or nature, or reveal unknown dimensions of common subjects and objects. I aimed for the latter and got some lacklustre shots of my pet cat, brooding art students and stunted coastal trees. The teacher gave me a C.

It’s taken decades to hone my own vision. By now, that teacher is likely dead. And the photographer ex has dementia. When we first met I was homeless and stayed in the flat he shared with two colleagues. All three spurned commercial work, using cameras for the same purpose that I made marks on a flat surface, and I admired their talent and drive. But shyness prevented my shooting strangers like they did, even if I’d believed in my ability. Most of the photographers we encountered were men. Ditto those whose genius graced my ex’s shelves. Women mainly featured as subjects or muses. And since I worked as an artist’s model, who was I to object? So I used my camera solely for snapping my art and, later, my partners. Never my ex, though he was photogenic – for fear he’d judge the result? Though we knew some colour photographers, they didn’t appear to impress him. And his photographer friends (all men) stuck to black and white too.

So I poured my passion for colour into drawing with pastels or painting. Until, thirteen years and three relationships later, a partner (not an artist) and I went halves on a Polaroid camera. He wanted to make erotica for instant gratification. Why not? And the aesthetic potential of Polaroids turned me on. That they developed themselves, while limiting, simplified the options, stimulating inventiveness. So when we split and divvied up our scant shared belongings, I left him the tent and kept the camera. But selfies (with no-one else at hand) were hard to control and, at $3 a pop, unsupportable on the dole. Yet my mind’s eye had opened and when, sixteen years hence, my current partner gave me a digital camera, I embraced colour again. But a pocket automatic is a far cry from an SLR, and the low-key results disheartened me. It took twelve more years to take my Canon seriously and to find a subject confining enough to force me back on inner resources.

John Berger, in a 1968 essay, argues that photography is not a fine art. Photos are infinitely reproducible, and so have no rarity value. Yet, socially, art functions as property. The former, if not the latter, is debatable. As are the distinctions he makes re how photos and paintings respectively relate to choice, formal arrangement and time. ‘There is no transforming in photography’, he sums up. ‘There is only decision, focus.’ And okay, I get how that could sound right to the left side of Berger’s brain. Yet for me, taking photos feels akin to and wholly continuous with making montages for a video or decades of drawing and painting. Creating images is a far cry from writing – these processes engage different parts of my brain – but the photographic impulse channels ideas and emotions I can express in no other way; ditto montage or paint. And isn’t that what bona fide artists do? Channel ideas and emotions into personal work that, by virtue of its uniqueness, can – at its best – touch the universal?

So, though Berger draws distinctions re the nature and function of the mediums, more key for me is that which divides original from derivative. And the loss of these distinctions parallels the rise of technological reproduction of images. What would Berger say if he could see where art is at today? Fifty years ago, controversy over an Archibald Prize winner painted from a photo got it disqualified. Now, who has time to paint from life? Hence, countless artists, even Archibald finalists, use photos, exploiting the mass appeal of photorealism. Yet the smoother the illusion, the less we sense the artist’s presence. Humans, in striving to imitate what technology can do, lose their humanness. And technology reciprocates by busting its arse to mimic us.

Spirit can’t enter this dense web of busyness. And yet it has to go somewhere. Disowned, lost to the mists of history or the collective unconscious, it reemerges as tech bro wizardry. We gaze into the funhouse mirror of AI and see an idiot savant that can crunch vast amounts of data at warp speed, yet can’t care, feel, love, fuck, roll around on the floor laughing its arse off or dream. What it can do is show us our future if we don’t wake from our trance: soulless disembodiment. Terminal banality. Did photography set the stage? AI can translate photos into information. But it can’t marvel at the vision of, say, André Kertész, whom my ex revered. Did he ever see Kertész’s surrealist Polaroids taken in old age? Unlike Kertész, my ex disdained to experiment; even once he’d begun to go gaga, he still swore by his old MO, scorning the digital revolution like he’d shunned the advent of colour.

Dementia: an umbrella term for a loose set of symptoms applicable to a wide range of degenerative physical or mental conditions. My ex and my mum both succumbed and, though his Graves’ disease as a risk factor contrasted her depression, they both clung to the past and feared change more than most. Could it be that such regressiveness – a worsening pandemic despite (or due to?) the dominant ethos of progress – accounts for the widespread need to mediate the flow of events from one moment to the next by capturing them to share on FB or Insta, or just to store in the cloud for a rainy day? As if to halt the hyperspeed flight of time so as to postpone the post-phone process of dying?

I have experienced photography a fine art. It has transported me at times the way any painting has done. There is as much room for the magic in photography as there is in any medium given the creative impulse and dedication.

You can say that again. Thanks for your perspective. I recently asked a gallerist why he doesn’t show photography as well as the usual paintings, mixed media, sculpture & prints, & he said he just sees it as ‘something different’. Yet at another gallery yesterday, I saw a show comprising photos along w/ sculptures made in response to them. To me, the sculptures felt wholly continuous w/ the black-&-white images, yet each piece, 2D or 3D, worked on its own terms.

I have experienced photography a fine art. It has transported me at times the way any painting has done. There is as much room for the magic in photography as there is in any medium given the creative impulse and dedication.