– Jeanette Winterson

‘Our options have changed,’ said the prompt last time I rang my bank. I recoiled. The inexplicably posh yet blank cadences of AI had replaced the prerecorded human voice. And to speak with a human, I would have had to join a queue: inconvenient, if less so than going to a bank. Besides, my local branch closed in 2024. Convenience isn’t an ‘option’, it’s the new world order. And convenience for corporations won’t serve us going forwards. As banks, telcos etc. sack more staff to maximise profits, leaving no-one to be accountable when things break down, we’ll increasingly wind up chasing wild geese in a virtual echo chamber of horrors. And if I’m mixing metaphors, well hey, it’s the future of language as AI eats more and more of its own excreta.

Meanwhile, it generates zombie-like voices and soulless, off-key images. Yet AI is ‘other’, says author Jeanette Winterson. The source of something truly other (recall classic horror stories) can be abyssal, microbial, alien, astral and/or divine. But digital technology originates from us. A self-professed optimist (read: wishful thinker on steroids?), Winterson also says it has no gender. Yet the prevalence of male AI engineers ensures gender bias at multiple levels. And AI was and is being raised on a diet of data collectively shaped by millennia of patriarchal dominance. Belief in its infinite potential to reinvent the wheel, or our destiny as a species, is at best misguided or naive. Far from being a clean slate, AI threatens to entrench age-old biases more deeply, not least because the emphasis on social justice themes in contemporary discourse – human rights, entitlement, DEI – boosts the illusion that humanity is advancing.

Yet the world bears witness to genocide in real time as our hallowed higher-ed institutions, once strongholds of the humanities, reward opposition to wrongthink at the expense of instructive debate while stifling robust protest over their arms investments. When Winterson says ‘we are becoming more self-aware as we work with AI’, does ‘we’ include enablers of its military uses? Collective progress towards such pressing goals as decolonisation or climate change mitigation is woefully slow, with increasing pushback from white supremacists, coal/oil/gas corporations etc. Yet we take the warp-speed rise of technology in our stride even as mainstream experts trumpet the risk that AI could one day nix us of its own volition.

Which, given enough development (so not just yet), is credible, if reminiscent of the vengeful Old Testament God who punished hubris with confusion, or corruption with destruction. Our civilisation has reached a pitch of decadence that history (not just the Bible) tells us precedes and leads to collapse; our instant gratification is dooming future generations. Last week a local boomer scoffed when I said our winters have gotten warmer. Is he losing his short-term recall to early-onset dementia? Or has dependency on air con dulled his senses? He tried to show me a video of a local diving spot on his phone, but I said I’d rather experience beauty directly. Ironic from someone who’s just spent a year pointing a lens at it. Still, I don’t delude myself that images can change their consumers.

Why, then, make art? It’s a way to fulfil the part of my psyche geared for transcendent experience. If all human souls bear a God-shaped hole (despite the dissent of Dawkins and co) and we don’t embrace a religion, we best reserve some wilderness or stillness to commune with spirit, or the high priests of science and technology will herd us into AIdolatry.

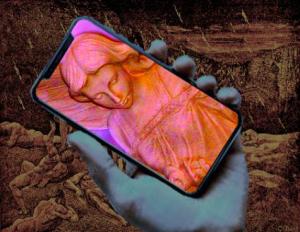

Can the mind of a man who spends hours each day on his smartphone be colonised without his knowledge? A friend who knows I’m working on a photographic project bragged about the shots he can take with his new phone. ‘Better than reality,’ he kept repeating gleefully. It sounds like a slogan for an ideal place to be. A heaven ruled by God or transhumanist elites? My friend showed off his full moon snaps. They struck me as brutally vivid. Clichéd. Entrepreneurial tech geeks seek to outdo reality. Yet art can, ideally, reveal it anew.

True, colonisation can yield consolations. Most of which prove addictive. Take violent settlers who spread deadly diseases, then ply the colonised with booze and processed food. Invasion isn’t just spatial, but psychic. Several levels of colonisation inevitably coexist, and none of us escape complicity. Caught in a web of hypocrisy, raised on colonist logic, we struggle (or not) to recognise how we too have been colonised: by Big Tech, Big Med, Big Ed, Big Oil, Big Ag, Big Science etc. – corporate parasites we can’t unite to fight as we side with the Left or the Right, even if they shape-shift, making a mockery of democracy. Our digital habit beats Aboriginal alcoholism. Indigenous youth overpopulate jails; ours chase their tails in a virtual wasteland.

Never content to just take land from locals, colonisers must break their spirit, enforcing new laws and imposing foreign religions. But when white men (and disenfranchised white women) invaded Oz, the long-established Indigenous inhabitants pushed back. And so began the massacres I never learned of at school, stuck in a classroom that shut out distractions like weather, wildlife, trees and whatever else a culture with Christian conditioning subjects to dominion. An education geared to suppress our instincts and alienate us from nature.

And yet it turns out that some of the thinkers I most respect are Christian. CS Lewis evinced such occult insights in his Space Trilogy that, reading it three decades ago, I never guessed. Others include an environmentalist writer – and former pagan whose conversion in 2020 surprised many (besides which, Covid rerouted countless lives) – and a neuroscience researcher whose faith doesn’t dictate his findings. Yet the idea of AI can challenge the most rational minds, and these latter two have come to associate it with evil.

Paul Kingsnorth posits AI as demonic, while Iain McGilchrist inveighs against its corporate crusaders. And, minus the Christian twist, I shudder with them to think of a future such as Winterson envisions. Yet, far from the entity – malign or benign – that so many suppose it to be, isn’t AI just an extension of our expansionist ethos? Our enchantment with so-called social media, data, speed and expedience? A logical next step in our accelerating trajectory from active to passive, cognisant to programmed, ensouled to cloned, reborn to uploaded? The idea that AI will somehow ‘surpass’ us (as it gets faster and eats far more data?) is a category mistake that credulous fantasists are more likely to make. AI too can ‘hallucinate’, but its confabulations lack meaning – to itself, not just to a sane human being. It can’t achieve nirvana, samadhi, or even an orgasm; won’t ever know the ecstasy of a lucid dream. And we’ve had to forget, or project, so much of our birthright to find AI enticing.

Brilliant, thanks Shane! xx

Thanks for reading & resonating, Tony!

I don’t seem to be able to leave a comment. Anyway, thank you for including a link to my work. I think we will have no choice with AI. The capitalist push for money and ‘the less messy engagement with people the better’ will win out. We’ve had some ghastly experiences with two lots of cleaner/gardeners over the last year – they use casuals who follow their ‘program’ on their mobiles and don’t necessarily have to know what they’re doing and there is no follow through when complaints are made about shoddy work because the same people don’t necessarily come back. Just sacked the first lot and the second lot are following the same system = robots and cheap labour…all appearing to be from the same pool.

Your comment came through, Annette. Many thanks. Your work is a valuable & unique resource – which can’t be said of much that now gets produced in our shortcut culture. AI wouldn’t be so easy to impose if we weren’t already so conditioned to dehumanising practices. I keep noticing how many customer service reps working under increasing pressure in highly competitive industries are starting to sound more robotic/programmed, even as AI (poised to steal their jobs) is starting to sound superficially more humanoid. Hard to imagine that this society isn’t bound for collapse.

Trying again via email. This just came my way on Linkedin which is relevant. From Michael West, independent journalist. “We need your help.

Over the past few months, our YouTube views and revenue have dropped by more than 30%. Not because the stories aren’t worth watching, but because YouTube’s algorithm has changed — and it’s burying independent journalism under a flood of AI-generated content.

We’ve always relied on real journalists telling real stories, fast, fact-checked, and human. But when algorithms prioritise clickbait and machine-made videos, the space for independent reporting shrinks.

If you want to help us push back, it’s simple: subscribe to our YouTube channel and turn on the notification bell. You don’t have to watch every video, but it tells the algorithm that people still care about real journalism — not AI slop.

Independent media survives because of you. Thank you for keeping us going.”

Thanks, Annette. West’s plea exemplifies the problem: we’re increasingly being force-fed AI-generated slop & deprived of real sustenance (following the industrial model of food production), & most consumers predictably just eat what’s put in front of them.

Yes brilliant. I’d love to know how Jeanette Winterson defines intelligence.

I experience AI and technology as a colonizing force. It gives me shivers.

Thank you for the synthesis of your insights

Thanks for your encouragement & engagement. How does JW define intelligence? She says it doesn’t need to be biological. And she talks about transcendence & the ‘invisible world’. And she talks about AI as ‘alternative intelligence’. She also describes herself as an optimist. 🙂

Thanks. ‘…alternative intelligence’ sounds like a cop out statement with no meaning. I don’t think intelligence need be biological either.

Agreed that intelligences exist beyond the biological realm. But I’m thinking of non-physical entities, not human-programmed neural networks. See below for a sample of AI’s characteristic smarmy drivel, which I just found by accident (because the algorithm favours it):

‘Jeanette Winterson, a celebrated author known for her works exploring themes of identity and transformation, has offered a captivating perspective on the future of artificial intelligence (AI). In an insightful piece covered by The Guardian, Winterson emphasizes the notion of AI as an ‘alternative intelligence’—a concept that extends our understanding of what it means to be human. Rather than perceiving AI as merely a technological tool, she advocates for recognizing its potential to offer a new lens through which humanity can explore its own capacities and limitations.

Winterson argues that AI’s unique ability to be ‘other’ is precisely what the human race needs at this pivotal moment in history. She suggests that as we face global challenges, the innovative and other-worldly thinking provided by AI could inspire solutions that might not emerge from traditional human thought processes. Her outlook contrasts sharply with the predominantly cautious or pessimistic narratives surrounding AI, positioning it instead as a harbinger of new possibilities for cultivating empathy and creativity.

In the Guardian article, Winterson’s viewpoint highlights the importance of embracing AI’s transformative power while remaining mindful of ethical considerations. She envisions a future where AI not only complements human intelligence but also challenges and expands it, suggesting that the collaboration between humans and machines could redefine creativity. By advocating for AI’s potential to enhance rather than replace human capabilities, Winterson offers a refreshing optimism amidst widespread concerns about AI’s impact on society.’

Yecch. Though to be fair, the actual Guardian piece has no substance either.

🫣I can’t imagine being optimistic about AI.